Hai ngày trước khi chiến tranh Việt Nam kết thúc, ông Lê Xuân Khoa và gia đình xuống phi cơ ở Mỹ để mở đầu cuộc sống mới. Lúc bấy giờ, Ông đang có một đời sống sung túc ở miền Nam Việt Nam, là Phó Viện trưởng Đại học Sài Gòn và đã là Thứ trưởng Bộ Giáo dục và Văn hoá [Việt Nam Cộng hòa].

Nhưng khi Bắc Việt gần thắng cuộc, ông biết là phải ra đi vì đã cáng đáng nhiều chức vụ cao cấp, biết chắc nếu ở lại sẽ phải vào trại cải tạo, bị cưỡng bách lao động nghiệt ngã, sức khỏe suy tàn, dinh dưỡng thiếu thốn. Nhiều người bị tổn vong ở những trại này trong đó có nhiều đồng nghiệp cũ của ông. Ở tuổi 47, ông cùng gia đình vợ và bốn con đặt chân đến thủ đô Washington DC, công việc làm đầu tiên là nhân viên thu ngân ở tiệm tạp hoá 7-Eleven rất xa lạ với những chức vụ ở Việt Nam. Trước khi tới Mỹ, tôi đã bảo các con tôi chớ ngạc nhiên nếu cha làm lao động phụ việc bên trời Tây này, vì chúng ta phải điều chỉnh cho thích hợp với cuộc sống mới ở Mỹ và chúng ta phải khởi đầu từ thấp để vươn lên cao hơn sau này, ông kể lại với đài truyền thông NBC Á-Mỹ.

Ông là một trong 133 ngàn người Việt tị nạn sang Mỹ khi Sài Gòn thất thủ năm 1975. Năm đó mở đầu cuộc di tản đông đảo của người tị nạn gốc Đông Nam Á, sau khi kết thúc cuộc chiến của Mỹ ở Việt Nam, Cambodia, Lào. Năm nay kỷ niệm lần thứ 45 người gốc Đông Nam Á tị nạn đến Mỹ, họ vẫn là cộng đồng đông đảo nhất đã định cư ở xứ này.

Miệt thị những người tị nạn

Khi những người Đông Nam Á bắt đầu đến Mỹ, họ vấp phải sự ác cảm và phân biệt chủng tộc. Dư luận chung lúc đó của người Mỹ là họ không ưa thích người tị nạn Việt Nam bởi cuộc chiến tranh đã kéo dài mà không ai muốn, trích lời ông Sam Vong, chủ nhiệm khoa Lịch sử người Mỹ gốc Đông Nam Á của Viện Bảo Tàng Smithsonian, và cũng là nguyên Phó giáo sư của Đại học Texas ở Austin.

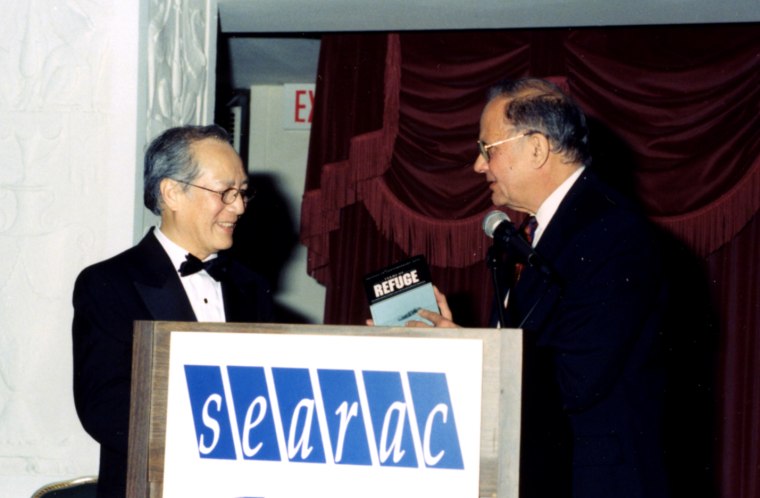

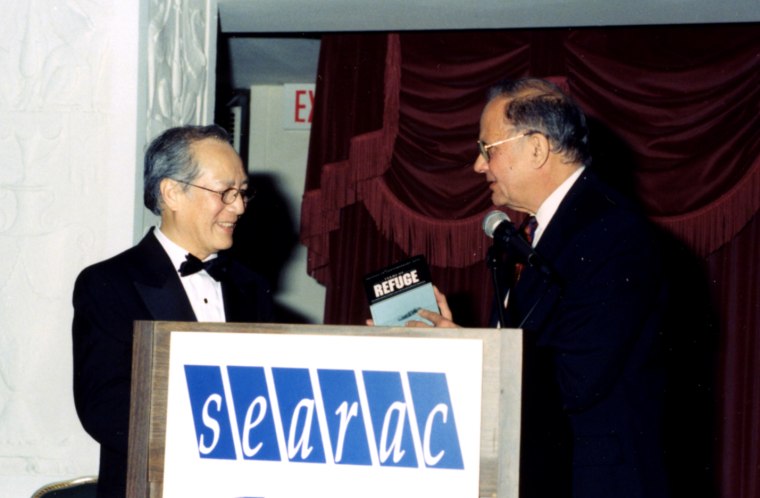

Theo một nhóm làm việc về nhân quyền và xã hội mang tên “Trung tâm Tài nguyên và Hành động Đông Nam Á (SEARAC)”, người tị nạn được coi là tự nguyện và nhanh chóng trở thành tự lực cánh sinh. Rất nhiều người bị dồn vào những khu ngụ cư nghèo khổ, chung quanh đầy bạo loạn, tranh chấp chủng tộc, trường học thiếu hụt. Tuy nhiên đó cũng là trường hợp khá phổ quát nhưng không phải ai cũng bị ngược đãi như thế, ông Vong nhận xét. Ông Khoa thích nghi với hoàn cảnh mới mà không hề phàn nàn. Gia đình ông được người bảo lãnh cho cư trú trong một năm và ông làm thu ngân vài tháng ở tiệm 7-Eleven. Sau đó năm 1979, ông làm Cố vấn ở SEARAC (lúc ấy mang tên Trung tâm hành động của người tỵ nạn Việt-Miên-Lào) và trở thành Giám đốc đầu tiên gốc Đông Nam Á của Trung tâm này. Đây là tổ chức khởi đầu do những chuyên gia Mỹ thành lập với mục tiêu trợ giúp chính quyền Mỹ (vì thiếu kinh ngiệm) để thiết kế những chính sách và chương trình trong việc tái định cư người tị nạn,

Tạo lập chương trình thống nhất để tái định cư người tị nạn

Khi những người tị nạn gốc Đông Nam Á bắt đầu đến Mỹ năm 1975, quá trình định cư được tiến hành một cách tạm bợ (adhoc) bởi Bộ Ngoại giao và nhiều tổ chức thiện nguyện. Vì thiếu hiểu biết về những vấn đề và nhu cầu của dân tị nạn, theo ông Khoa, nhiều người đã coi đó là một gánh nặng cho xã hội Mỹ. Vì thế ông chú trọng làm sao chuyển đổi từ thù địch sang ủng hộ bằng cách xác định là tị nạn vì lý do chính trị chứ không vì lý do kinh tế. Theo SEARAC, ông Khoa làm việc với Quốc hội và giới Truyền thông để công chúng Mỹ nhận thức ra rằng tại sao người tị nạn phải rời bỏ quê hương họ và tại sao Mỹ cần phải tiếp nhận họ.

Eric Tang, tác giả cuốn sách “Sự bất ổn của người tị nạn Cao Miên trong khu ổ chuột thành phố New York” lưu ý rằng những người này đau khổ vì bị chấn thương bởi chiến tranh và sinh sống trong các trại tị nạn. Họ đa số đến Mỹ những ngày đầu năm 1980, thoát ra khỏi nước này sau cuộc diệt chủng với 2 triệu nạn nhân, theo ông Vong. Ông ta kể thêm là những người tị nạn Lào, Miên đã bị di chuyển rất nhiều lần trong đất nước họ. Các bạn không thể chờ đợi những người này tự lập và khởi đầu xây dựng cuộc đời chỉ sau ba tháng. Phải mất nhiều phen tìm việc, điều chỉnh với môi trường xã hội mới mẻ, sum họp gia đình. Họ cần sự giúp đỡ của xã hội, cần sự hỗ trợ tài chính và tài nguyên cộng đồng để tự đứng vững trên bàn chân mình.

Một bước ngoặt lịch sử xảy ra năm 1980 với Đạo luật về tị nạn, biểu quyết bởi lưỡng đảng ở Quốc hội, đạo luật này do ông Khoa soạn thảo và chủ chương tái định cư nay được chính thức hoá. Nó nhằm giúp người định cư tự lực về kinh tế trong vòng ba năm, theo ông Vong.

Đạo luật này đã làm tăng lên cái ngưỡng trần, hàng năm số người tị nạn được chấp nhận từ 17400 đến 50000 trong hai năm từ 1980 đến 1982.

SEARAC tháng Ba vừa qua đã làm lễ kỷ niệm 40 năm Đạo luật tị nạn ra đời và ghi nhận đã tái định cư được trên 1.1 triệu người gốc Đông Nam Á sống ở Mỹ.

Di sản của Lê Xuân Khoa

Bà Đinh Quyên, hiện là Giám đốc điều hành của SEARAC (thế hệ thứ hai sinh ở Mỹ, cha mẹ di tản năm 1980), ghi nhận nhờ ông Khoa mà hơn một triệu người di tản từ Đông Nam Á đến định cư ở Mỹ. Các gia đình họ tăng trưởng sinh con đẻ cái rồi tiếp sức tài trợ cho các gia đình đến sau được đoàn tụ.

Do khả năng lãnh đạo của ông, đã hình thành Văn phòng “Tái định cư người tị nạn” để tinh giản sự định cư không những cho Đông Nam Á mà cho cả mọi người tị nạn khác từ năm 1980, bà Đinh viết trong một bức điện thư.

Ông Khoa về hưu ở SEARAC từ năm 1996 nhưng vẫn cố vấn cho tổ chức này. Bà Đinh kết luận vài thập niên đã qua, di sản của ông Khoa vẫn tồn tại trong sự nghiệp xây dựng và huy động tổ chức của chúng tôi. Những thể hệ tiếp theo vẫn ủng hộ để sao cho những cộng đồng tị nạn bị tác động bởi sự bất bình đẳng kêu gọi cần thay đổi.

P.X.Y.

***

Nguyên văn

How Southeast Asian American refugees helped shape America’s resettlement system

2020 is the 45th anniversary of Southeast Asian American refugees’ arrival in the U.S., still the largest group to be resettled since then.

April 21, 2020, 3:12 AM +07

By Agnes Constante

Two days before the end of the Vietnam War, Le Xuan Khoa boarded a plane with his family to start a new life in the United States.

He’d had a comfortable life in South Vietnam. He was the vice president of the University of Saigon and had served as the country’s deputy minister of culture and education.

But as the North Vietnamese came closer to claiming victory, he knew he had to leave.

Given his high-ranking positions, he was certain that if he stayed, he would have been sent to a re-education camp where he would have been subject to grueling hours of labor, poor health care and insufficient food. Many people died in these camps, including some of his former colleagues, he said.

Khoa was 47 when he stepped foot in Washington, D.C., where he settled with his wife and four children.

He landed his first job in America as a cashier at a 7-Eleven, a far cry from his positions in Vietnam.

“Before coming to the U.S., I told my children, ‘Don’t be surprised if I have to start with menial jobs in the West because we need to adjust to a new life in the U.S., and we have to start very low in order to come up later,’” he told NBC Asian America.

Khoa was one of 123,000 Vietnamese refugees who came to the United States after the fall of Saigon in 1975. The year marked the beginning of the mass migration of Southeast Asian refugees following the end of conflicts the U.S. had been involved in in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos.

The Southeast Asian American refugee community this year is observing its 45th anniversary in the United States, where they remain the largest group the country has resettled since then.

When Southeast Asians began arriving in the United States, they were met with hostility and racism.

“The general sentiment of Americans was that they didn’t want Vietnamese refugees in the U.S. because of this very long and unpopular war,” said Sam Vong, curator of Asian Pacific American History at the Smithsonian Institute and former assistant professor of Asian American history at the University of Texas, Austin.

According to the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC), a civil rights group, refugees were viewed as voluntary migrants,and were expected to quickly become economically self-sufficient and independent. Many were resettled in impoverished neighborhoods and were surrounded by gang violence, racial tension and poor schools.

This experience was common for many refugees, but it wasn’t the case for everyone, Vong said.

Khoa described adjusting to his new life with no complaints. He and his family were assigned a sponsor who gave them a place to live for a year, and his stint at 7-Eleven only lasted for a couple of months.

He eventually began working at SEARAC in 1979 – which was called the Indochina Refugee Action Center at the time – as a consultant before becoming its first Southeast Asian director.

The organization, established by American professionals, aimed to help the U.S. government design refugee policies and programs because it had limited experience in resettling Southeast Asians, according to SEARAC.

Creating a unified refugee resettlement program

When Southeast Asian refugees began arriving in the U.S. in 1975, the country’s resettlement process was conducted ad hoc by the State Department and voluntary organizations.

And without an understanding of their problems and needs, many were considered a burden to American society, Khoa said.

So he focused on shifting the narrative around Southeast Asians from hostility to support by redefining the community as political refugees rather than economic migrants. He worked with Congress and the media to educate the public about why they fled their countries and why the U.S. should receive them, according to SEARAC.

Eric Tang, author of “Unsettled: Cambodian Refugees in the NYC Hyperghetto,” noted that refugees suffered trauma from war and from the experience of living in refugee camps.

Cambodian refugees, the majority of whom began arriving in the U.S. in the early 1980s, had come out of a genocide that claimed some 2 million victims, Vong said. He added that many Cambodian and Laotian refugees had also been displaced multiple times from their home countries.

“You can’t just expect refugees to just pick up their lives and start rebuilding their communities right after three months,” he said. “It takes some time to find a job, to get adjusted to their new environment, to relocate family members. And that requires both social support, financial assistance, and any other kind of community resources to help people get back on their feet.”

A historic moment came in 1980 with the passage of the Refugee Act, a bipartisan bill Khoa helped draft that formalized the country’s resettlement procedures. It established a goal of helping refugees achieve economic self sufficiency within three years, Vong said. The act also raised the ceiling for annual refugee admissions from 17,400 to 50,000 from 1980 to 1982.

SEARAC in March commemorated the 40th anniversary of the Refugee Act and credited it for the resettlement of more than 1.1 million Southeast Asian Americans in the United States.

Quyen Dinh, executive director of SEARAC and the daughter of Vietnamese refugees who arrived in 1980, credited Khoa for the America she and more than 1 million other Southeast Asian refugees have experienced, where refugees see their families grow by having children and sponsoring other family members through family reunification.

“It was his leadership that led to the formation of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, streamlining the resettlement of not just Southeast Asians but all refugees since the 1980s,” she said in an email. Khoa retired as SEARAC’s president in 1996, but remained an adviser to the organization.

“Decades later, his legacy lives on in our organization’s mission to build and mobilize this, and the next, generations of advocates so that those most impacted by inequity in our communities are the ones calling for change,” Dinh said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

A.C.